Sir Paul Edmund Strzelecki left behind such an impressive list of achievements that it is

hard to believe that it concerns one man.

He was born in 1797 in Głuszyn in Greater Poland. Since childhood, he dreamed of long journeys, so it is

hardly surprising that he chose to study geography and geology at the University of Heidelberg, which he did

not complete, however. After returning to the country from university, he began to collect funds for future

voyages, so he became the administrator of the estate of Prince Franciszek Sapieha. It was then that a

"misfortune" befell him, which perhaps determined his entire later life. Paweł fell in love, and it was

mutual, with Adyna Turno.

Unfortunately, Konstanty Sczaniecki, another noble man, also tried to marry Adyna. Her father decided that

she

can only marry Konstanty. He hoped that marriage to the wealthy Sczaniecki would improve the declining

family

finances. Apparently, Paul and his beloved one decided to flee the country, but the girl's vigilant father

prevented them. Strzelecki, left his hometown with a broken heart and, as he later wrote, "due to an unhappy

love affair", he left Poland forever.

Since misfortune often hides good fortune, after the death of his employer, Prince Sapieha, Strzelecki

received a great fortune, which he later multiplied, among others by trading grain. He could travel wherever

he wanted, almost without limits.

He was 34 years old when he left Poland forever and came to England. There, according to some biographers of

the traveler, he continued his geological studies at the University of Edinburgh. Some sources say that he

also studied at the Faculty of Geology at the University of Oxford, where he additionally deepened his

knowledge in the field of petrography, hydrology, botany, anthropology and ethnography.

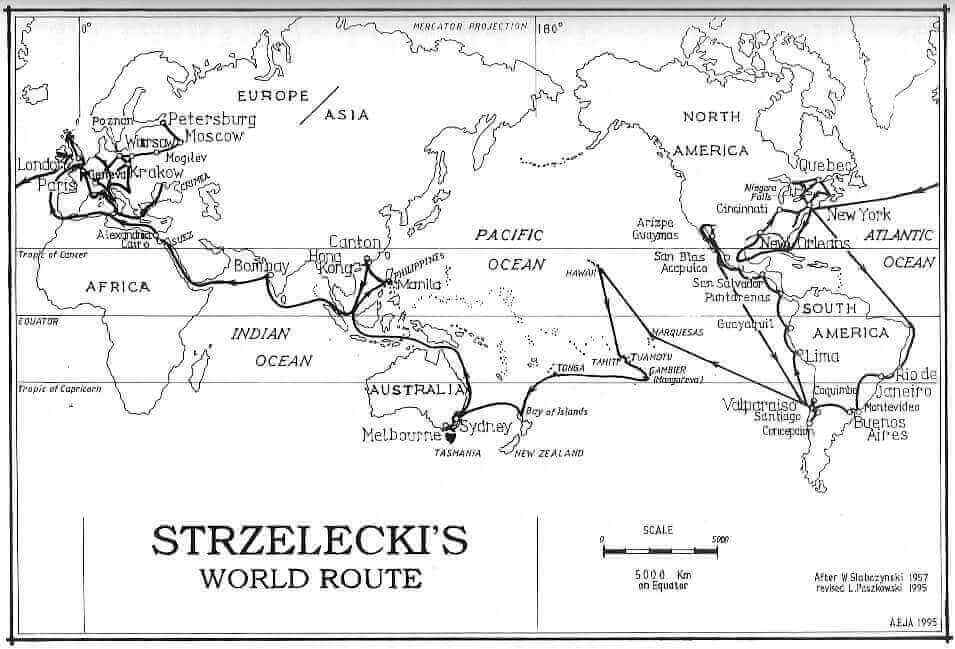

North and South Americas

On June 8, 1834, he left Liverpool, England, and sailed to New York to begin geological

work in the mountainous areas of the Appalachians in North America. This was the beginning of a journey

around the Earth that was to last 9 years.

He covered all costs from his own pocket. His passion for

learning about the world and its resources made him give up his comfortable life and devote his entire

fortune to a scientific journey around the world.

After several months of research in the eastern US, Strzelecki crossed the Canadian border. There he

discovered copper deposits that are still exploited today. The further route led through Mexico, Cuba and

Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina, up to Chile. Here he again undertook mining and geological work. But it still

wasn't enough. He now made a ten-month cruise along the western coast of South America to California and the

Pacific. He visited the Marquesas, Hawaii and Tahiti, and in 1839 he reached the coast of New Zealand. An

impressive journey, considering what the means of transport were like back then.

Australia

On April 25, 1839, the 42-year-old traveler arrived in Australia. At his own expense, he

decided to conduct research on the mineralogy of the continent here. Georg Gipps, the governor of the then

British colony, although he accepted the research program, did not rush to support the work financially.

Strzelecki started research. In order: the Blue Mountains and the Australian Alps in the Great Dividing

Mountains, which stretch along the eastern coast. In the Australian Alps, he conquered the highest peak on

the continent. On March 12, 1840, he stood on the top of an unnamed mountain.

A dozen or so days later he wrote to Gipps that the sight of its top struck him because of its similarity to

the Kościuszko Mound in Krakow:

"However, in a foreign country and on foreign soil, but among free people who value freedom and its

defenders, I could not refrain from naming the mountain Mount Kosciuszko."

Thus, Australia's highest mountain (2,228 m above sea level) was named after a Polish hero and patriot, the

leader of the 1794 Insurrection. But Strzelecki did not stop at naming the mountains. Now he has done

something very personal. One of the peaks of the Blue Mountains was named after his beloved - Mount Adine.

The traveler still hasn't forgotten his old love. He wrote letters to her during all his travels, and one of

them was accompanied by a flower picked from Mount Kosciuszko.

The Australian natives held him in high esteem. He fought for equal rights for all. He was clearly against

calling the natives "savages", maintaining that "Europeans are greater cannibals than those to whom they

themselves give this name." He is etched into Australian history forever. His greatest discovery was

"Gippsland", named after the colony's governor, a fertile land located to the south-east of the Snowy

Mountains and full of various riches: coal, oil and gold deposits, the Latrobe Valley.

The discovery of the expensive metal was such a sensation that the governor, fearing the outbreak of a gold

rush that could cause riots, forced the Pole to keep the discovery a secret. Although this meant losing the

due gratification, Strzelecki agreed to Gipps' proposal. This decision would later cost him the loss of

priority in discovering one of the greatest resources of the new continent. The prize for discovering gold

was awarded ten years later, despite many protests, to an Englishman, Edward Hammond Hargraves.

Five years of research on the continent have produced tangible results. A geological map of eastern

Australia and Tasmania was created at a scale of 0.25 inches per mile. It had impressive dimensions: seven

meters long and one and a half meters wide, and was the largest and most comprehensive compendium of

geological knowledge about the continent.

Already during his stay in America, Strzelecki became known as a staunch opponent of the slave trade. He

helped the starving population of Ireland, which was affected by famine in the mid-19th century. He came up

with the idea of unemployed peasants settling in Gippsland. He was interested in the fate of women

wandering around London, and he also helped them settle in Australia. As John Lort Stokes, a British

scientist and traveler, later wrote - "only the lack of water and food could have turned Strzelecki off the

road." He traveled on foot, carrying essential items in his backpack. To honor the Pole's efforts, Stokes

named the Mountain of Fatigue, the highest peak in a mountain range in southeastern Australia - which was

named the Strzelecki Mountains. Two peaks, a lake and a river were also named after the traveler. The route

of the Pole's Australian journey is also dotted with towns bearing his name. In the 1920s, seven obelisks

commemorating the discoverer were erected in Gippsland, and in 1988, in Jindabyne, his monument by Jerzy

Franciszek Sobociński was unveiled. There is an inscription on the plinth: "Sir Paul Edmund Strzelecki

1797-1873 The Polish Explorer of Australia".

England

Health problems forced Strzelecki to return to England in October 1843. He spent the next two years writing

his monumental work "Physical description of South Wales and Van Diemens Land" - the 500-page work became a

scientific bestseller and was the most important source of knowledge about Australian nature and geology for

several dozen years.

Sir Paweł Edmund Strzelecki, awarded the Gold Medal of Discovery, member of The Royal Society of London,

honorary doctor of the University of Oxford, lord by the will of the British Queen Victoria, died on October

6, 1873.